“Some retorted upon me, ‘There are heathen at home; let us seek and save, first of all, the lost ones perishing at our door.’ This I felt to be most true and an appalling fact; but I unfailingly observed that those who made this retort neglected those home heathen themselves.”-John G. Paton

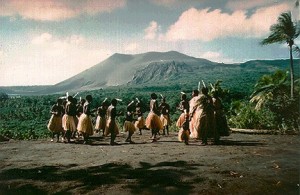

John G. Paton was a pioneer missionary to the New Hebrides, an island chain in the south Pacific which is now modern-day Vanuatu. During his time there he faced much opposition, though eventually through vigorous and difficult labor many came to know Christ. His life has proven to be an inspiration to generations of missionaries and his passion for the glory of Christ among the nations shines within the books written about him, especially in his autobiography. There is no doubt that Paton’s legacy endures to this day in our methods, mindset, and in our conduct regarding missions. Through careful examination of the works written about him we can divulge the source of the courage that characterized Paton’s life and the hope of salvation for all peoples that drove him to the New Hebrides.

Paton was born in Dumfries, Scotland on May 24, 1824. His family came from the tradition of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland and it is noted that they hardly ever missed a service. Indeed, Paton’s father was known to have missed service only three times. [1] At home, daily family devotionals and his parents’ desire to lay a solid foundation defined Paton’s childhood. It was from his parents that he learned to fear the Lord and fostered a deep affection for the glory of God. Paton recounts his early days fondly as he writes, “We had, too, special Bible readings on the Lord’s Day evening−mother and children and visitors reading in turns, with fresh and interesting question, answer, and exposition, all tending to impress us with the infinite grace of a God of love and mercy in the great gift of His dear Son Jesus, our Savior.”[2]

Much of Paton’s school years were devoted to learning. Even at a young age he was determined to serve God as a missionary and desired to see the lost come to salvation through Christ. He writes, “These spare moments every day I devoutly spend on my books, chiefly in the rudiments of Latin and Greek; for I had given my soul to God, and was resolved to aim at being a Missionary of the Cross, or a Minister of the Gospel.”[3] It was not long before Paton was offered a position in Glasgow, along with a free year at the Free Church Seminary. This meant that Paton would have to leave his beloved childhood home. He had to walk the first forty miles of the way to Glasgow before taking the railway the rest of the way. His father walked with him for the first six miles. They talked, prayed, and finally, wept together. As Paton looked back after parting from his father, he saw him continue to pray for his son as he went on his way. Paton was deeply moved as he went on his way and vowed, “deeply and oft, by the help of God, to live and act so as never to grieve or dishonor such a father and mother as He had given me.”[4]

After a brief period of teaching and ill health, Paton was appointed as a Glasgow City missionary. While Paton’s tenure in this position was successful, it was also a period of persecution. He was threatened, had stones thrown at him, reviled by the newspapers, and hated by the local priests. Yet despite all of this his ministry continued to grow as did the number of people coming to know Christ. [5] Soon, however, the lure of the foreign mission field became too strong for Paton to resist. After much prayer and deliberation Paton gave himself to become a missionary to the New Hebrides with the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland. [6] His decision was not met without opposition. One older man even told him, “The cannibals! You will be eaten by cannibals!” This was actually a valid reason to be concerned as less than twenty years previously two London Missionary Society missionaries were killed and eaten shortly after landing of the island of Erromanga.[7] Paton was not deterred. He famously responded to the older gentleman, “Mr. Dickson, you are advanced in years now, and your own prospect is soon to be laid in the grave, there to be eaten by worms; I confess to you, that if I can but live and die serving and honoring the Lord Jesus, it will make no difference to me whether I am eaten by cannibals or by worms.”[8]

Indeed, it was this passion to serve and honor the Lord Jesus that would keep Paton alive for the next several years. He left Scotland shortly afterwards for the island of Tanna in 1858. His first four years on the island were wrought with danger and heartbreak, especially after the death of his wife and infant son within his first year on the island. [9] The environment was horrifying to Paton. He had never seen such warring, disease, and death in all his life. Yet his response was not to run away, but to have compassion for them. He resolved to learn the language as well as possible in order to share Christ with them.[10] Paton’s compassion, however, was not returned. The fact that many of the white men who had come to the islands to deliberately spread measles did not help. More than one third of the inhabitants of the island were killed, including one of Paton’s converts and some of his indigenous teachers. This only fueled the Tannese hatred of the Europeans, and Paton was no different than the others in their eyes.[11]

Even in the face of danger and great sorrow Paton went about his duties in sharing Christ with the Tannese. On one occasion he found himself surrounded by an angry mob of armed men who were determined to kill him. Paton’s response was to fall to his knees and pray. He writes, “I knelt down and gave myself away body and soul to the Lord Jesus Christ, for what seemed the last time on earth. Rising, I went out to them and began calmly talking about their unkind treatment of me and contrasting it with all my conduct towards them.” The response of the chiefs who were there was astounding. They decided that they would not kill Paton. The persecution still did not stop there. Men would follow Paton around with loaded muskets, charge at him with axes, and try to spear him to death.[12] Eventually the situation on the island became so bad that Paton was forced to leave Tanna. He faced criticism for this decision, even from his friends who told him that he should have stayed and died. Paton believed that it would be better and more worthwhile to live and serve God another day. The subsequent years would prove this to be true.[13]

After serving on Tanna, Paton would travel to continue to raise support. He also worked to gain new recruits for the mission field and also secured a new ship for missions, the Dayspring. He remarried and spent time preparing to return to the New Hebrides once again. However, seeing as it was not possible to return to Tanna, he instead planted his life on the island of Aniwa. Here he would spend the next fifteen years of his life.[14]

Paton’s time on Aniwa proved to be most fruitful. After years of labor, droves of Aniwans became Christians. Looking back on his work on Aniwa, Paton remarked, “I claimed Aniwa for Jesus, and by the grace of God Aniwa now worships at the Savior’s feet.”[15] Though his time there proved to be fruitful, it was not without difficulty. Paton was once again amongst a people who were driven by revenge as opposed to grace; he was once again among a people who trusted in their gods to bring him to an end. In fact, one of the biggest reasons they allowed him to come was because he had some valuable supplies. They believed that once their gods killed him they could take what they wanted.[16] Despite the repeated dangers, Paton continued to go about his work and he found a need that could be met: the need for a source of fresh water on the island. He decided that he would then dig a well. Many of the islanders thought he was foolish to search for water in the ground. Still, Paton continued to dig until water was finally uncovered in the earth. One of the chiefs, Namakei, spoke to the people about the well, stating, “The Jehovah God has sent us rain from the earth. Why should He not also send us His Son from Heaven? Namakei stands up for Jehovah.”[17]

The effect was astonishing. People brought forth their idols and had them destroyed by any means necessary. The whole of society was transformed by the newfound faith of the Aniwans. The Holy Spirit swept across the island and people came to rejoice in the Lord. Finally, after much suffering and difficulty and seemingly fruitless labor, the harvest had come. The church continued to grow strong and healthy and Paton was amazed at how the people desired the Lord and wanted to serve Him forever. After all this, Paton left the island and only returned a few times, though the people remained close to his heart. However, his service did not stop with Aniwa.[18]

Paton would continue to serve by travelling all over the world and raising money to have more missionaries sent to the New Hebrides. His autobiography awoke an intense desire in many to follow Christ wherever it may lead. Many congregations passionately supported missionaries and saw how God could be at work among even the most unimaginably morally deficient heathens. In the meantime Paton would also continue to translate resources into the Aniwan language, including the New Testament.[19] He continued to preach to congregations up until the very end of his life, even through much pain in his final days. On January 28, 1907, John Gibson Paton passed away.[20]

What can be said of Paton’s life? Indeed, he was a man of great courage. John Piper notes that this courage was rooted in a sense of divine calling as he writes, “That sense of duty and calling bred in him an undaunted courage that would never look back.”[21] Paton was indeed convinced of this call as he states early in his life, “The Lord kept saying within me, ‘Since none better qualified can be got, rise and offer yourself!’ Almost overpowering was the impulse to answer aloud, ‘Here am I, send me.’”[22] Even though he was so sure of this calling, he still resolved to present his desire to God in prayer. Piper writes of Paton’s prayer life, “This is what Paton trusted God for in claiming the promises: God would supply all his needs insofar as this would be for Paton’s good and for God’s glory.”[23]

Paton was a man who was consumed by God’s grace and a desire to be obedient to him. Let his life be an encouragement to those who would give their lives to serving and honoring the Lord Jesus Christ. Paton’s story is not so much about Paton as it is about how God is sovereign and in control of all situations. Many of Paton’s methods for reaching the people are used to this day, including taking the time to learn the local language, using humanitarian aid to bring the gospel to a people, and church planting as a means to reach a people group. Most of all, all of this was driven by prayer and a desire for God to be glorified among all peoples. Christ was at the center of Paton’s desire to see people saved. Now, there are many who lived in the New Hebrides who will be represented around the throne of God, singing praises to Him forever.

[1] John D. Legg, “John G. Paton: Missionary of the Cross,” Five Pioneer Missionaries: David Brainerd, William C. Burns, John Eliot, Henry Martyn, John Paton (London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1965), 306.

[2] John Gibson Paton and James Paton, The Story of John G. Paton: The True Story of Thirty Years among the South SeaSea Cannibals (London: Hodder and Stroughton, [1898?]), 19.

[3] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 21.

[4] Ibid., 25−26.

[5] Legg, “John G. Paton,” Five Pioneer Missionaries, 307−308

[6] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 40−41

[7] John Piper, Filling up the Afflictions of Christ (Wheaton: Crossway Books, 2009), 53.

[8] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 42−43.

[9] Biographical Dictionary of Christian Missions (Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1998), 519.

[10] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 50.

[11] Legg, “John G. Paton,” Five Pioneer Missionaries, 313−315.

[12] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 78-80.

[13] Legg, “John G. Paton,” Five Pioneer Missionaries, 319

[14] Ibid., 318−323.

[15] Piper, Filling up the Afflictions of Christ, 57.

[16] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 207.

[17] Legg, “John G. Paton,” Five Pioneer Missionaries, 326−327.

[18] Ibid., 330.

[19] Ibid., 334−335.

[20] Ibid., 338.

[21] Piper, Filling up the Afflictions of Christ, 73.

[22] Paton, The Story of John G. Paton, 40−41.

[23] Piper, Filling up the Afflictions of Christ, 77.